Unpaved Beauty: Fast-growing Loudoun has not lost its dirt roads or rural charm

Richmond Times-Dispatch, July 21, 2016

STORY BY BILL LOHMANN PHOTOS BY BOB BROWN

As one of the fastest-growing counties in America, this is Loudoun County:

- A population that has more than doubled since 2000 with a quarter of its residents foreign-born.

- Seemingly endless suburban Washington sprawl and mind-bending traffic.

- Dulles International Airport.

But this also is Loudoun County:

- Acres and acres of fields, farms and forest, rich in history and unrivaled scenery, a rural refuge in the heart of Northern Virginia and the capital, some would say, of Virginia’s horse country.

- More than 40 wineries and tasting rooms.

- And, perhaps most astoundingly, about 300 miles in unpaved roads, the most of any county in Virginia — which is not exactly what you might expect to find in a county with Loudoun’s reputation for explosive growth.

“What I love about living here is finding new roads,” said Rich Gillespie, executive director of the Mosby Heritage Area Association, a regional nonprofit preservation and historic organization, and a longtime resident of Loudoun.

He has been finding new roads for 40 years. A graduate of William & Mary, Gillespie was on his way to western Loudoun in the 1970s — not exactly sure how to pronounce the name of his new county — to take a teaching job when his car died. He purchased a new one but didn’t have the money to buy a radio, so he spent his free time — he also couldn’t afford a television at home — driving around the countryside. New wheels in a new place.

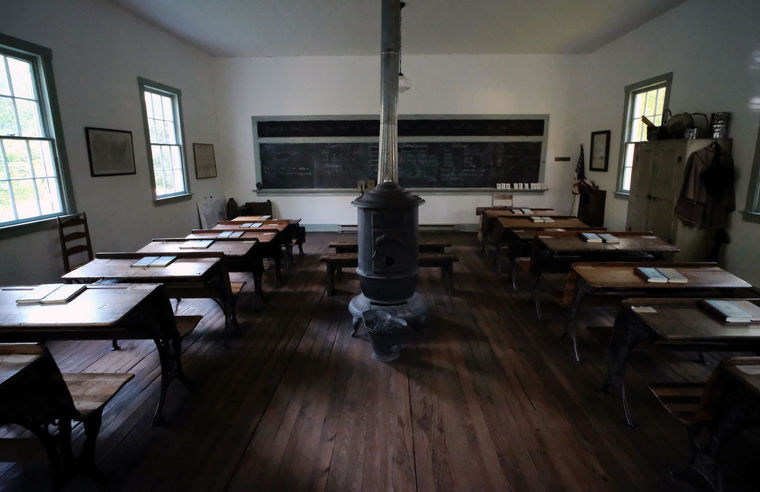

It turned out the fledgling history teacher had stumbled into a historian’s wonderland: Civil War battlefields, old churches, one-room schoolhouses.

“Just an incredible concentration (of history),” said Gillespie, who landed and still lives in the western part of Loudoun, parts of which look much the way they did decades, even centuries ago. “I thought, ‘Aren’t I lucky? I’m going to teach history in a place that has all this stuff.’ ”

A Tale of Two Counties

Loudoun, the fastest-growing county in Virginia, is almost a tale of two counties: the hyper-developed east of Dulles/suburbia and the preserved rural west, with farms and subdivisions abutting one another as the two worlds come together. County planners by design have attempted to keep Loudoun in both worlds.

Wealth runs throughout Loudoun. The county had a median household income of more than $122,000 in 2014 — more than double the national median household income — ranking it No. 1 nationally in 2014 among jurisdictions with a population of 65,000 or greater. Politically, Loudoun has become a critically important swing jurisdiction that helps decide statewide elections because of its continued suburbanization and demographic diversity.

Our visit to Loudoun started when Bob Brown and I met Jim Person while doing a story on his family’s ancestral church in Southampton County. “You should do a story on the back roads of Loudoun County,” he said.

Loudoun — a county that has gone from a population of 24,000 in 1960 to more than 370,000 today — has back roads? Yes, indeed it does. And a lot of them, as it turns out, don’t have a lick of asphalt.

Person is a Richmond native who retired in 2014 as principal of Loudoun’s Stone Bridge High School after almost four decades as an educator in the county. He arranged for us to meet Gillespie, his friend and former colleague (and fellow W&M alum) who is a retired award-winning history teacher who taught at Loudoun Valley High for 30 years. The two of them spent an afternoon and evening driving us around western Loudoun, showing us the sights, telling us stories and introducing us to a few of those unpaved roads.

On the Road Again

When Person moved to Loudoun from Richmond in the 1970s and encountered the many dirt and gravel roads weaving through the western part of the county, he thought, “You’ve got to be kidding me!”

Now, he accepts them as part of Loudoun’s character — and something, as it turns out, to be preserved.

Loudoun came to have an abundance of unpaved roads through “partly bad luck and partly good luck,” said Mitch Diamond, a member of the Loudoun County Preservation and Conservation Coalition who sits on the subcommittee for Loudoun’s rural roads.

“In the 19th century, we were poor so the roads stayed the way they were,” Diamond said. “In the 20th century, people came to live on these wonderful farms out here, and the roads were an asset. If you go to equestrian communities around the country, you find similar networks of unpaved roads. The equestrians really treasure them, so they become valuable.”

Besides the fact dirt is easier on horses’ hooves than pavement, the unpaved roads radiate a certain beauty unspooling across the countryside and threading through wooded hillsides, bending this way and that over meadows and past old stone fences. You feel blessed for living in the midst of such beauty, Diamond said, and the roads are a big part of that.

“They’re historic and charming,” he said. But they also can be dusty and bumpy and prone to potholes and ruts if not properly maintained.

“We’re not Luddite; we want the roads to be well-cared for,” said Diamond, noting the subcommittee on rural roads was formed to ensure just that. “They are really important to our economy.”

Tourism is big business in Loudoun, and the county has much to offer: wineries, craft breweries, pick-your-own farms, farm-to-table cuisine and destination restaurants, equestrian events, bed-and-breakfasts, luxury resorts and pretty drives. U.S. 15 runs north and south through Leesburg, the gateway to Loudoun’s wine country and in some ways the dividing point of the county: East of Leesburg is much of the development and, to the west, says Jennifer Sigal of Visit Loudoun, the county’s tourism arm, “the land starts opening up.”

And if all that isn’t enough, Loudoun was named “The Happiest County in America” by SmartAsset this year based on its low unemployment and poverty rates and having the fourth-highest income ratio among the 1,000 counties in the study. Loudoun’s next-door neighbor, Fairfax County, was No. 2.

We met Gillespie at the Mosby Heritage Area Association headquarters at Atoka, the Rector House where Confederate cavalry commander John Singleton Mosby’s unit formed in the parlor. We sat on the porch talking as traffic streamed past — the Rector House is in Fauquier County “by a smidge,” Gillespie said — but this is hunt country, on each side of the line, with all that comes with that description. A pickup truck blew past, closely followed by a Bentley.

We piled into Person’s SUV and commenced a whirlwind tour that included:

- The National Sporting Library and Museum in Middleburg, a world-class library and fine-art museum focused on equestrian and field sports.

- A spin along some of the ancient, unpaved roads that might look like long personal driveways but are truly public roads, though often narrow. In the face of oncoming traffic, you learn to move over to the right. Quickly.

- The Middleburg Training Track, built by Paul Mellon, philanthropist and owner of Thoroughbred racehorses.

- The Unison United Methodist Church, where the congregation retreated to the basement when the Union and Confederate forces launched the Battle of Unison during a church service in 1862. The church became a makeshift hospital, and the graffiti of wounded soldiers remain on the walls of the balcony.

- Goose Creek Stone Bridge, a 200-foot-long span built around 1810 that was the center of fighting in 1863 during the Battle of Upperville and carried vehicular traffic — including tractor-trailers — until it was replaced by U.S. 50 in the 1950s. Nearby U.S. 50 remains a busy thoroughfare across Loudoun, carrying commuters traveling between Washington and Winchester and all points in between.

We drove past old plantations and through Quaker villages, such as Lincoln; old African-American communities, such as St. Louis; and Waterford, a Quaker village along Catoctin Creek that is designated as a National Historic Landmark district. The Waterford Fair, a step back in time, is held every October.

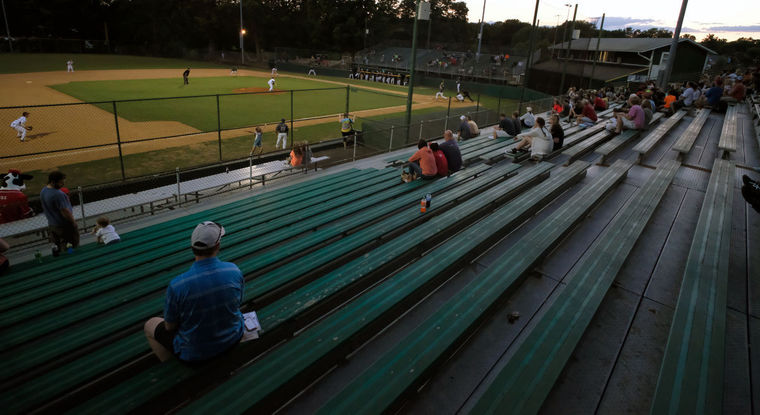

We wound up in the small-but-up-and-coming town of Purcellville (pronounce it with the emphasis on the first syllable, and the locals seem to slide right over the first two Ls altogether, as in PURSEH-ville), where a Valley League baseball game was underway at Fireman’s Field. Dinner was at Magnolias at the Mill, housed in a former mill, in Purcellville. History while you eat.

“What we try to do is get people out on these back roads with places they can stop and touch history,” said Gillespie, not necessarily speaking of places with admission fees. “But places you can get out and walk around: a churchyard or a battlefield or an old bridge.

“Almost every single place I drive, I don’t drive more than a mile without coming on another story, another historical place that has an amazing tale to tell.”